Preface: The Idea for this essay came to me during my trend forecasting course; we were discussing how the French Revolution marked the first time in history when the bourgeois class intentionally dressed “down” to blend in with the proletariat for survival, which reminded me a lot about contemporary high-fashion. And with the recent “controversy” over Balenciaga’s new “Paris” sneaker, I thought this was a perfect time to write this paper.

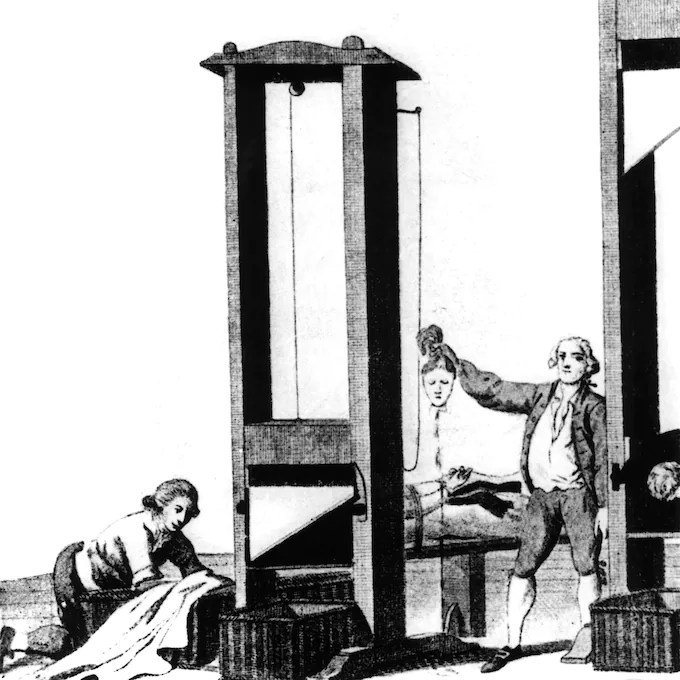

Towards the end of the French Revolution, a new trend became very popular among (what was left of) the French aristocrats (bourgeoise). This trend had been growing slowly for years but reached its peak following the Reign of Terror in July 1794. This trend focused on informality and simplicity, a great contrast to the grandiose fashion that emphasized their class and wealth prior to the French Revolution. Following the (justified) killing of many of this bourgeois class, the remainder felt the importance of understating their wealth and blending in amongst the common folk (proletariat). This class camouflage reminds me of what many contemporary high-fashion brands are doing today: intentionally designing clothes to make the wearer look as if they’re middle or lower class, whether it’s tame “norm-core” or oversized, distressed, and deconstructed styles.

Another example of this “bourgeois camouflage” was during the 2008 recession. While the working class was losing their jobs, homes, and livelihoods, designer and department stores saw little-to-no decline in luxury sales, but they did see a change in what consumers were buying and how they were shopping. Ron Frasch, the president and chief merchandising officer of Sak’s Fifth Avenue during the recession, said that customers were purchasing fewer logo-heavy items and flash items, instead favoring simplistic and minimal designs. One rumor stated that Hermés had customers leaving retail stores with brown paper bags in lieu of their signature orange bags. When talking about this rumor Christin Binkley, a fashion writer for the Wall Street Journal, said, “It doesn’t even matter whether it was true or not; the mere fact of those rumors reflected people’s response: it was suddenly so uncool to look rich. This time also saw the rise in the uniformed CEO, where a billionaire would cosplay as one of their serfs but in abhorrently expensive versions of casual Friday staples. The two most infamous examples are Steve Jobs with his black turtleneck (of which he owned 100+), which cost just under $300, and Mark Zuckerberg with his $300 Brunello Cucinelli t-shirts. These CEOs were praised for being smart with their money by want-to-be capitalists, despite the prices of the garments being outrageous.

More recently, we’ve seen this happening again; during COVID-19, the American top 1% stole $50 trillion from the bottom 90% in one of the largest wealth transfers of all time. Despite our economy “shutting down” and over a million deaths in the US alone, billionaires seemed to only benefit from the pandemic. In the subsequent protests over civil rights and wealth inequality, we once again saw little decrease in luxury sales (and in some cases, increased sales), but we did see a change in what customers were buying. Brands like The Row, Loro Piana, Brunello Cucinelli, and Hermés saw increases in sales during and “post”-pandemic. These brands are classified as “coded-luxury” brands that release simple clothes that could be mistaken for the Banana Republic but at disgustingly high prices, like Loro Piana’s $500 cashmere baseball cap.

Going back to Christina Binkley’s quote about The Great Recession, it became uncool to look rich; we see this sentiment reflected in street styles as well. During the recession, the US government decided to give away money to bail out the companies that had created the recession instead of to the citizens affected by the recession, which, paired with wealth inequality levels approaching the levels of pre-revolution France and the US being in the top 10 of highest per-capita homelessness, resulted in many members of the working class contemplating whether capitalism and the rich actually had the working class’s best interests in mind (they don’t).

Over the last ten years, we’ve seen a decrease in support of capitalism and a surge in support of socialism. In a 2021 poll from Axios/Momentive, 41% of voting Americans viewed socialism positively, a 2% increase from 2019. In the same study, Americans that viewed capitalism positively fell from 61% in 2019 to 57%. After recovery from the recession, we saw a massive influx of brands designing clothes that made the wearer appear in a “lower” social class. Brands like Fear of God (2013) and Yeezy (2015) pioneered this “poverty-core” look of tattered and faded graphic tees and hoodies and ripped jeans. Although these pieces looked like they could be purchased at a thrift store for $5, they were 10 to 20 times that price. In and out of the fashion community, a common joke was that people were paying outrageous prices just to look homeless.

Once again, following the pandemic, we’ve seen another rejection of dressing like you’re rich—this time with preowned workwear, oversized clothes, a rise in thrifting, and distressing. This time, instead of Yeezy and Fear of God at the head of these trends, It’s Carhartt and Balenciaga. Much of Demna Gvsalia’s work for Balenciaga fits this “poverty-core” aesthetic: extremely oversized garments and ironic graphics resemble fast-fashion garments, commonly found discarded at thrift stores. Most recently, the “Paris” sneaker (the name of the shoe feels almost too perfect for this paper) that he designed caused much controversy: Many people in-and-out of the fashion world were outraged to see a destroyed Converse replica selling for almost $2000; nevertheless, people still bought it.

I think this mindset shift comes for differing reasons to the various classes. For the working class, as Binkley said, it was no longer cool to be rich; the rich were the ones causing these economic problems for the working class, and to dress like them and continue to praise them would be against their interests. But for the bourgeois, I think this shift was more sinister. Not only was it not cool for them to look rich, but it was not safe for them to look rich. If they were to follow the actions of the aristocrats during the French revolution and continue flaunting their money, there could be more civil unrest, and they could potentially cause another uprising. So they learned from the aristocrats and hid their wealth by buying non-descript garments.

Sources

Baukham, Andrew. “Mass Protests and Demonstrations Surge 36% Globally in Decade Following 2008 Financial Crisis | Chaucer Group.” Chauncer Group, 19 July 2021, http://www.chaucergroup.com/news/mass-protests-and-demonstrations-surge-36-globally-in-decade-following-2008-financial-crisis.

Brooke, Eliza. “The Great Recession Inspired Minimalism in Clothes, Homes, and Branding.” Vox, 27 Dec. 2018, http://www.vox.com/the-goods/2018/12/27/18156431/recession-fashion-design-minimalism.

Esguerra, Clarissa. “French Revolutionary Fashion.” LACMA Unframed, 3 Aug. 2016, unframed.lacma.org/2016/08/03/french-revolutionary-fashion.

“Income Inequality by Country 2022.” World Population Review, worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/income-inequality-by-country. Accessed 15 June 2022.

Lakin, Max. “The $300 T-Shirt Mark Zuckerberg Didn’t Wear in Congress Could Hold Facebook’s Future.” W Magazine, 12 Apr. 2018, http://www.wmagazine.com/story/mark-zuckerberg-facebook-brunello-cucinelli-t-shirt.

Laver, James. “Fashion During the French Revolution | Encyclopedia.Com.” Encyclopedia.Com, http://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/culture-magazines/fashion-during-french-revolution. Accessed 15 June 2022.

Martinez, Marina. “Vive La Révolution: Comparing U.S. Inequality with 1789 France.” Polljuice, 21 Sept. 2020, http://www.polljuice.com/vive-la-revolution-comparing-u-s-inequality-with-1789-france.

Silva, Chantel de. “Support for Socialism Gaining Traction in US, Poll Suggests.” The Independent, 28 June 2021, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/americans-socialism-positive-axios-poll-b1874049.html.

“State of Homelessness in America.” The United States Council of Economic Advisors, Sept. 2019, http://www.nhipdata.org/local/upload/file/The-State-of-Homelessness-in-America.pdf.

Sullivan, Aline. “Luxury Brands Covet the Recession-Proof.” The New York Times, 7 Mar. 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/07/style/07iht-mluxe.1.10800096.html.

Times, The New York. “Covid in the U.S.: Latest Maps, Case and Death Counts.” The New York Times, 14 June 2022, http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html.

Twersky, Carolyn. “How Coded Luxury Has Taken Over Fashion and Pop Culture.” W Magazine, 5 Jan. 2022, http://www.wmagazine.com/fashion/coded-luxury-tiktok-bottega-veneta-succession.

Weissmann, Jordan. “U.S. Income Inequality: It’s Worse Today Than It Was in 1774.” The Atlantic, 21 Sept. 2013, http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/09/us-income-inequality-its-worse-today-than-it-was-in-1774/262537.